THE MARS DILEMMA

/This NASA video shows a concept animation of how one proposed Exploration Zone on Mars might work.

An excellent new article in Scientific American describes a meeting last October that gathered together dozens of the world’s most committed proponents of a manned mission to Mars. They hoped to be able to choose the landing site for the NASA Mars mission planned for twenty years from now, or at least come up with a shortlist. They didn’t.

There are a huge number of important factors to consider in the selection: they need a landing site that’s not too high in elevation (or the thin air will hamper the use of a parachute) and not too low (thicker air will hold too much dust kicked up during the rocket landing and cause problems); a site close to the poles will be too cold and get too little sunlight, plus the rotation speed of the planet near the equator gives an extra boost to a departing spacecraft for the trip home. Producing rocket fuel for the return trip (from water) is essential—some places it would have to be processed from the soil using heat, or squeezed from rocks; places farther north or south likely have groundwater or ice under the surface, but they have disadvantages mentioned above. Areas already studied by the Mars rovers and other craft are well-known, with lots of data gathered over the years, but there’s something to be said for exploring new territory too. The Scientific American article covers all of those issues very well.

But one aspect of the Mars discussion might be even more of a roadblock than the selection of a landing site—the dilemma about microorganisms.

If there is some form of life on Mars—and answering that question is one of the main reasons for going there—there’s the risk that astronaut explorers will disturb some soil or rock, or thaw some ice, and release organisms native to that world which could find their way inside the habitat, maybe inside the astronauts themselves, and eventually back to Earth. It’s unlikely that precautions and decontamination measures would be 100% successful in preventing that, and there’s no way to know what kind of risk such life might pose to forms of life here on Earth. An alien ebola for which our immune systems have no defence? That’s an alarmist view, but not impossible.

Then there’s the other side of the coin: protecting Mars from contamination by us.

The United Nations Outer Space Treaty of 1967 forbids the harmful contamination of celestial bodies. Every spacecraft that goes to Mars has to undergo (and survive) rigorous sterilization procedures, which accounts for a substantial part of the costs of such craft. And that’s just metal and circuits—what about living bodies? Some researchers claim that the human body supports ten times as many bacterial hitchhikers inside and outside than the number of the body’s own cells. How can we possibly be sure of not leaving some of those bacteria behind on Mars? If the planet is utterly barren, the risk that our Earth bacteria might survive and spread might not seem like a severe consequence (except for violating the space treaty). But what if there is life on Mars? It will probably be in the form of microorganisms inhabiting the subsurface ice and damp soil, managing to survive under very challenging conditions. There’s a significant chance that the Earth bacteria we unleash could be deadly to Mars life outright or simply provide too much competition for scant resources.

We might discover the first known form of life elsewhere in the universe, only to find that our explorations have condemned that life form to death.

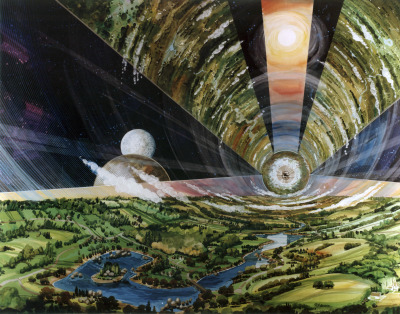

There’s an outside chance that we could dodge these problems with one very carefully regulated visit to the Red Planet. There’s no chance at all that we can ignore them if we ever establish permanent habitations there. So before we ever colonize other celestial bodies, we’ll have to decide whether it will be a one-way trip for the colonists (to prevent the contamination of Earth) and whether or not we have the right to spread our own form of contamination throughout space.

If you’ve read many of my blog posts you’ll know that I think it’s critically important for humanity to establish a presence beyond Earth—our small planet is just too fragile, and we’re too vulnerable here—but it may be that we’ll have to confine our migration to places that are unquestionably devoid of life.

On one hand we’d love to know that we’re not alone—that life has arisen elsewhere in the universe, but if it has, we may have to protect it from ourselves by staying away.

A dilemma indeed.