PHILAE HAS LANDED

/

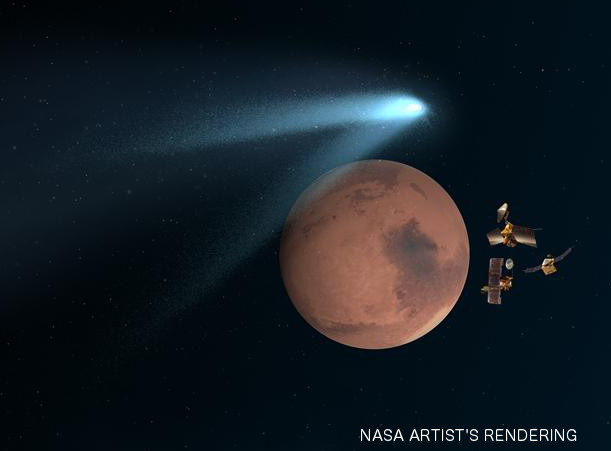

Photo taken by the Philae lander on approach.

There were cheers and tears and hugs all around at the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft Mission Control. The Philae lander successfully made the first-ever landing by a man-made object on a comet at 11:04 am EDT. This is the biggest moment in a mission that was launched in 2004. The lander quickly began to send telemetry to confirm contact and that it still has power, although the landing didn’t go exactly as planned. Because the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko was expected to be soft and granular, and its gravity is negligible, the Philae lander carried harpoons that were programmed to fire upon landing and anchor the small probe to the ground. It’s now known that those harpoons did not fire, and Philae may have bounced once when coming down (the landing site isn’t totally flat, and the craft hit the surface at about human walking speed). Fortunately the landing gear also included screws that would gently dig into the comet material to hold Philae down, and it appears that at least some of the screws have dug their way in. Talk about mixed emotions, reaching the pinnacle of a ten-year mission and not being completely certain the Philae will hang on!

More information will have to wait until Thursday when the craft and the comet are in the proper alignment with Earth again, but so far the mission team has a lot to be proud of.

Assuming the best scenario, Philae will soon dig samples of the comet and we’ll finally find out what comets are really made of. That will be important information about the early stages of the solar system, when comets formed, and might be invaluable knowledge for when we send spacecraft to mine the asteroids and outer moons. Some comets might turn out to be handy fueling stations.

As much as anything else, the Rosetta mission is encouraging because it shows how much can be accomplished through broad multinational cooperation. There are a lot of partners involved in this venture, from a lot of different nations—not just Europe. And hopefully each one will get to enjoy the many scientific rewards in the days to come.