DISASTER STORIES: MORE THAN JUST A GUILTY PLEASURE?

/I love disaster stories.

I usually explain it by saying that disaster scenarios bring out the best and the worst in humanity, which makes for terrific character-building and storytelling potential. Heroism and sacrifice, but also the self-serving villains we love to hiss and boo at. While fantasy novels let us imagine what it would be like to live in such a world, disaster stories are more than just guilty pleasures: they make us dig deeper, to ask ourselves “What would I do in such a situation?”

That’s my theory. Or maybe I’m just a little twisted. No psychoanalysis, please.

The first SF disaster novel I remember reading was J.G. Ballard’s first novel The Wind From Nowhere. Though he later pretty much disowned it (and it might suck if I were to re-read it now) I was impressed at the time with the image of a world ravaged by an ever-growing wind, and the noble attempts of mere humans to survive it. John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids is still one of my all-time favourite books, in which most of humanity is stricken blind and the carnivorous, mobile, and perhaps even intelligent triffid plants gain the upper hand. It’s simply chilling, told in an understated British style. In fact, UK writers seem to have produced many more disaster novels than those from other English-speaking countries. In the US the disaster genre has found its expression more often in the movies (although some, like Michael Crichton’s terrific The Andromeda Strain succeeded on both paper and film). While Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle combined their talents to tell about a mammoth comet impacting the Earth in the 1977 novel Lucifer’s Hammer, it’s probably not as well known as the two movies with similar plots Deep Impact and Armageddon both released in 1998 (because Hollywood likes to run with themes).

Which brings me to my second point about disaster stories. There’s a sub-genre of science fiction that can be called “cautionary tales” that describe how things can go wrong as a warning to all of us. Brave New World, 1984, and Fahrenheit 451 are classic examples. And disaster stories are cautionaries at full blast. While some plots involve a purely natural threat, like a solar flare-up or a killer rock from space, many others (nuclear melt-downs, deadly plagues, and nanotechnology run riot) point the finger at potential man-made disasters. Not only do they warn us about paths we shouldn’t take with our technology, but also how critically important it is to be prepared for when disaster strikes.

Especially since the 1990’s there have been significant efforts to detect and plot the orbits of Near Earth Objects—things like asteroids and comets in our space neighbourhood that could potentially strike the planet with destructive results. And yes, there’s been serious discussion about how to send a rocket crew out to blast a threatening rock away from its collision course, just like Bruce Willis and the boys. The Spaceguard Foundation based in Italy, the UK’s SpaceGuard Centre, and other projects continue to work in the field, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy in the US recently released a National Near-Earth Object Preparedness Strategy from a working group that involved many different federal agencies. It’s the kind of collaborative approach that’s needed to cope with disasters on a national, or even global scale.

Society’s collective mindset is important—we have to believe that a given scenario is plausible before we will think about ways to protect ourselves from it. Science fiction fertilizes that soil. Perhaps we’re more prepared for crises like the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak because of pandemic-themed stories like Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, Stephen King’s The Stand, or Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. A huge number of nuclear holocaust novels, from Shute’s On The Beach to Frank’s Alas, Babylon to Zelazny’s Damnation Alley help to keep the pressure on world leaders for nuclear disarmament (apparently Donald Trump doesn’t read). Of course, lots of novels and movies about rogue artificial intelligences and nanotechnology run amuck have ensured a very active public discussion about those areas of research and restrictions that should be considered.

Think tanks and government agencies collectively spend millions organizing brainstorming sessions to prepare for potential disasters of every description. Maybe their first step should be to stock up their SF libraries. Yes, I’m being a little facetious, but I’d like to believe that our literature of the imagination has helped to create a mindset that will save many lives in the centuries to come.

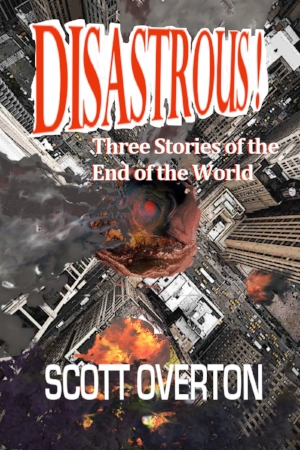

Have I written disaster stories myself? Of course! I invite you to read my collection Disastrous! Three Stories of the End of the World available as a free ebook download from my website bookstore or from Kobo. (I made it free on Amazon too, but they put the price back up!)

Enjoy!