SPACE MINING AND THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

/

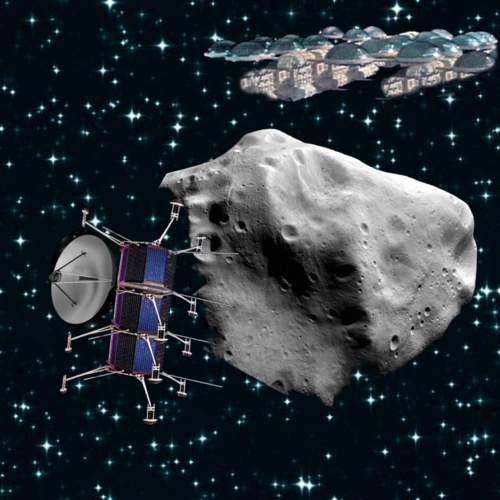

The US senate just passed some legislation that will make space mining more attractive to private companies. Or at least it will if other countries follow suit. The legislation, called the “Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act of 2015” still has to pass one more round in the American congress and then approval by US president Obama in order to become law. Among its most important features, it will give companies the rights to the material they mine from asteroids, though the companies could not actually own an asteroid. That’s similar to the model that mining companies use on Earth—they may not actually own the land, but their mining rights mean they own the resources they extract from that land. Private companies like Planetary Resources are already cheering this latest news. Why not? It’s not like any government can afford to get into space mining on its own.

Mind you, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 says, among other things, “No one nation may claim ownership of outer space or any celestial body.” So it would be a bit questionable for the US to unilaterally grant companies mining rights to celestial bodies that the United States cannot, by treaty, own. That part of the new legislation will be meaningless unless other countries agree to it. Fortunately, those who drafted the bill were careful to make clear that it does not mean the US is claiming sovereignty over any celestial body by granting such rights.

Will we want space mining companies to be like the big mining companies on Earth? Doesn’t it kind of rankle to think of wealthy companies and individuals being given special rights to something that is no more theirs than it is ours? A parallel on Earth would be companies mining on government land—land ostensibly owned by all citizens, including its resources. Yet only the mining companies’ shareholders profit, not citizens (except for the minimal taxes that are collected on any surface buildings). That model came from a time when we couldn’t imagine anyone wanting the patches of distant wilderness where mining companies set up their operations, and we didn’t worry about the places we lived being affected by anything such companies did so far away. But with large scale pollution we’ve discovered that Earth isn’t such a big planet after all. The concept of companies being responsible to remediate land they’ve torn up and polluted is a pretty recent development, and I don’t expect any early space legislation will force businesses to tidy up an asteroid and put it back the way they found it once they’ve extracted all of the metals or water. Who would care? For now.

Mining operations in space will have to be largely self-policing, not only regarding their industrial practices or pollution, but also in the way they treat labourers. Just as governments can’t afford to build and operate mining facilities in space, they can’t afford a constant police or military presence either. And anyone who thinks a phone call will bring the cavalry swooping in within a day or two has never studied physics. So we may be allowing private corporations to set up their own fiefdoms without much prospect of serious oversight. I’m reminded of any number of movie westerns with powerful landowners and downtrodden ranch folk!

Unlike a parcel of land on Earth, where a company’s pollution or damming of a river might cause serious harm elsewhere, an artificially-controlled asteroid or any broken-off parts could become the ultimate planet-killing weapon. It’s not easy to see who should be entrusted with that capability. And that same potential risk means that asteroid mining might not be practical for actually providing resources for those of us on the surface of the Earth. It wouldn’t be especially costly or difficult to sling blobs of ore or metals back to the home planet, but the potential consequences of a mistake are so horrific, who could ever afford the insurance coverage? It doesn’t bear thinking about what could be done with such facilities in the hands of maltreated workers, rioting prisoners, terrorists, megalomaniacs, or any other “bad guys” you could name.

OK, but wait now…haven’t I always sounded like I was in favour of asteroid mining and other space activity by private companies? Yep.

The fact is, we’ll never be able to build colonies away from Earth, or starfaring spaceships, without mining the materials out there—it’s simply too expensive to carry it all up from down here. Governments will never be able to afford to spend the kind of money involved to mount those mining operations, and it isn’t their job. So it will have to be done by private companies.

I just think it’s important to look at all of the implications of technological progress. And I like to point out the scary stuff. That’s what writers do.

On a totally different front, I’ve often written here about space colonies (including my last post) and I deeply want to believe we’ll someday colonize worlds around other stars. Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2015 novel Aurora is a compelling account of a generation ship sent to create just such a colony, and the things that go wrong. I highly recommend it as a great read, but you should also read this excellent feature essay by Robinson on Cory Doctorow’s blog explaining why such colonization will never happen.

I really wish he hadn’t done such a good job of it.