CATCHING UP ON MY READING

/ When I buy books I like to support real book stores because I don’t want them to disappear, but I have to say that when I visit the Science Fiction section of our local Chapters store (Chapters-Indigo is the big book chain in Canada) I’m pleased to see many of the classics of the genre and also disappointed to see how many of the newer books are novelizations from the Star Trek and Star Wars universes, or other media. Here are some that aren’t.

When I buy books I like to support real book stores because I don’t want them to disappear, but I have to say that when I visit the Science Fiction section of our local Chapters store (Chapters-Indigo is the big book chain in Canada) I’m pleased to see many of the classics of the genre and also disappointed to see how many of the newer books are novelizations from the Star Trek and Star Wars universes, or other media. Here are some that aren’t.

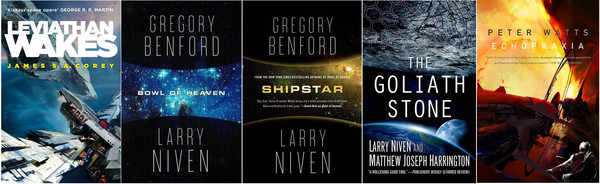

Leviathan Wakes by James S.A. Corey (a pseudonym) is the oldest of my recent reads, published in June of 2011. It’s a really well done space opera. If you like stories of adventure in space with high stakes on the line, memorable characters in tough scrapes, and believable settings without a lot of hard science, there's nothing wrong with that and this book will satisfy. It's well written, and you'll probably want to know what else is in store for these characters, which is just as well because it's the first of a series called The Expanse that now includes three sequels and two other novels set in that universe.

I’ve always been a Larry Niven fan, and Ringworld is one of my all-time favourites, so when I saw Niven back in the giant-artefact-building game in collaboration with another great writer, Gregory Benford, I figured it would be a must-read. Bowl Of Heaven came out in 2012 and it’s second half Shipstar a few months ago. They are two halves of one book—you can’t read one without the other. This time the mega-world is a giant bowl cupping a sun and using plasma sprayed from the sun for propulsion. There’s a gargantuan landscape, vivid and imaginative aliens, lots of hard science, and yet, as some have commented, it feels as if Bedford and Niven are inventing ever-more-strange aliens by the end just because they didn't know how to otherwise resolve the plot's main questions. I originally gave the books three stars, but I think I’d bump that to 3 ½ just to recognize their prodigious imaginations.

I’d probably give that same rating to another Larry Niven collaboration, this time with Matthew Joseph Harrington. The Goliath Stone is about another big thing: an asteroid being brought to Earth by newly-aware nanobot entities following their original programming with a twist of their own. A lot of the story is also about how nanotechnology could transform our own bodies. And the science is detailed, but never bogs down the plot, which is lightweight anyway. What makes The Goliath Stone a great choice for a quick read is that it's that rare animal: a science fiction thriller of sorts that's loaded with humour—sly witticisms, bad puns, sex jokes, and tons of pop literary references that will keep you amused all the way through.

Which brings us to the heavy lifting of the recent crop, and also my favourite. I’m a longtime fan of Peter Watts, the Canadian marine biologist-turned-author, and his Blindsight was an amazing book, so I was excited to learn there was a sequel on the way. Echopraxia doesn’t include any of the same characters but it tells the story of Blindsight’s alien incursion into our solar system from a different perspective. Watt's books are wedged full of hard science and ingenious speculations drawn from it, yet this book is very strongly about faith (OK, even if God is compared to a virus). It also features zombies and vampires, but they’re not anything you’d recognize from TV shows. The main character, Brüks, is a top research biologist, yet he’s the slow-learner in the cast. The scope and breadth of Watts' research and the searing edge of his prose are nothing less than stunning, but I sometimes feel you'd need a Mensa IQ to truly get all of it. I enjoy it, and recommend it to any hard SF fan, but don’t ask me any questions about it for a while. At least until my brain cells stop smoking.

You can read more of these, and other reviews anytime at my Goodreads page.