A NEW GOLDEN AGE OF SPACE EXPLORATION?

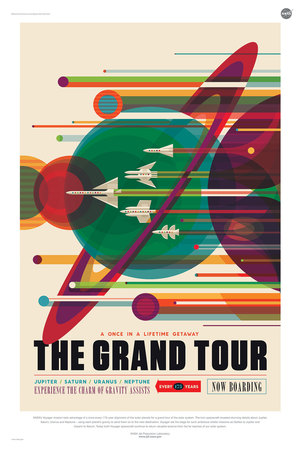

/Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Unless you keep up with current space news, it may be easy to feel that the Golden Age of space exploration is behind us. After all, the last time humans set foot on the Moon was the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. Heady stuff, but really, there hasn’t been much going on since, has there?

Actually, the amount of space exploration that’s been happening in recent decades is astonishing. It’s just that almost none of it has involved human crews. The one major exception is the International Space Station, which recently marked twenty years in space (its first components and first occupants were launched in November 1998). It’s been continuously manned since November 2000, and has hosted 227 crew and visitors, some as many as five times. It’s operated by a partnership of five space agencies (representing 17 countries) and has been visited by citizens of seventeen different nations. I’m not sure which is its most important contribution: the amount of data the ISS accrues every single day about how humans can live and work in space, or what it teaches us about the international cooperation needed to make us a spacefaring species. Nonetheless, because the ISS has been around for twenty years, and we can even watch it go by overhead, the general public probably underestimates its importance and may simply have lost interest.

So what else has been going on?

2004 may seem like a long time ago, but do you remember the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko? We watched its Philae lander drop toward the barbell-shaped object with fascination, and held our breath as it bounced and ended up at a angle that prevented it from collecting solar energy, which spelled its doom. But we did witness comet off-gassing and a snowstorm. Then in January 2005 NASA’s Deep Impact mission visited two other comets, 9P/Tempel and 103P/Hartley.

The Dawn spacecraft was deactivated just one month ago after visiting the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres (in the asteroid belt), producing amazing photos and detailed maps of these remnants of the solar system’s formation (or possibly fragments of a planet that broke up). It was also an important test of ion thrusters for propulsion instead of standard rocket motors.

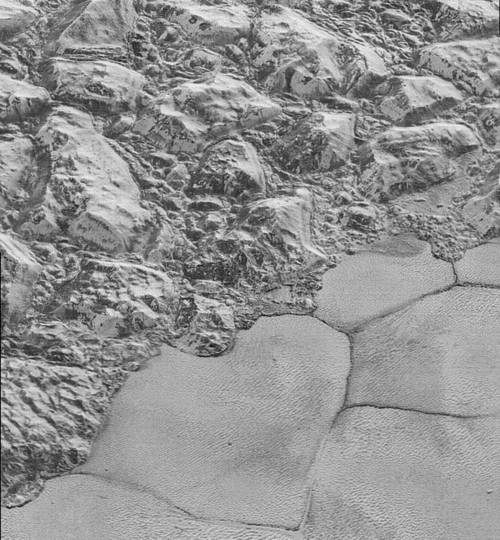

NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto was a huge success in 2015 when it sent back photo after brilliant photo of the icy world and its moon Charon, after already providing fantastic imagery and data from Jupiter and the Jovian moons in 2007 en route. But New Horizons isn’t done yet. It’s speeding its way toward a Kuiper Belt object designated as 2014 MU69 (nicknamed Ultima Thule, meaning beyond the farthest horizon) and will reach it this coming New Years Day (Jan. 1, 2019). Such objects are also thought to be leftover material from the solar system’s formation, probably slush and ice balls—after all, that’s the region most comets come from.

Although it met its end a little over a year ago (Sept. 15, 2017), deliberately plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere, can we forget the awesomely majestic pictures provided by the Cassini-Huygens probe? It spent thirteen years exploring Saturn, its moons and its rings, and the results were astounding.

Fast forward to this year: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe was launched in August 2018 and will fly through the outer atmosphere of the sun, known as its corona, seven times closer to our star than any spacecraft before it. But the big attention this week was the successful arrival of the InSight lander on Mars, which is tasked to penetrate into the Martian soil and probe the crust of the planet for the first time. Because of the high risk of failure, the landing got ‘live’ coverage and lots of media attention when it succeeded.

Yet we shouldn’t forget two more asteroid missions: the Japanese Hayabusa2 spacecraft, which has dropped a small lander onto an asteroid named Ryugu and is still in orbit there, and the NASA OSIRIS-REx probe that will arrive this Monday Dec. 3, 2018 at the asteroid Bennu. (Both of these asteroids are called “diamond-shaped” but they remind me of those old pressed charcoal briquettes for the barbecue!)

In the meantime, there have been lots of missions within the Earth-Moon system, and the U.S. is working with private companies and other countries toward a return by humans to the Moon by 2023. Closer to home, there have been important advances in rocketry, especially from Elon Musk’s company SpaceX. The SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket is capable of launching satellites, and then landing safely back on Earth, enabling it to be re-used (most recently on Nov. 15th). This is a vital advancement toward making commercial uses of space affordable. And, of course, the SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, the most powerful launch vehicle in current use, ostentatiously launched a Tesla Roadster into space Feb. 6, 2018 on its first test flight, carrying a mannequin nicknamed Starman in a space suit at the wheel.

Why is all of this important? What are the benefits?

If you’re reading a blog like this, you probably don’t need a sales pitch. But the more we learn about how the cosmos, our world, and our species came about, the more we can predict where we will all go from here. That’s just good survival protocol. Exploratory missions to comets and asteroids in particular are potential goldmines of information about the early solar system, but also may answer the question of how life arose on Earth, since scientists speculate that life here may have come from “out there”. They could also bring us closer to understanding how to protect ourselves from extraterrestrial microorganisms drifting down onto our planet from the far reaches of space. Not to mention identifying potential collision risks to our home from all of the celestial objects whizzing through the solar system.

The more we can learn about how humans can survive, thrive, and work in space environments, the closer we come to making use of them in ways that will benefit all of us. Conditions of zero-gravity, readily-available vacuum, and deep cold can facilitate the production of medicines and other exotic substances very difficult to make on Earth. Mining of asteroids, the processing of ores, and other manufacturing processes performed in space could bring much needed relief to the stressed environment of Earth. If we can find other places to live, or adapt other places to make them liveable for humans, we can help ease the population pressure on our home planet and, maybe more importantly, ensure that humanity would no longer be at risk of extinction from a planet-wide disaster.

Even the process of all this exploration is beneficial. Partly because of the cost in resources, material, monetary, and mental, large-scale endeavours like these demand international cooperation at government and corporate levels, but also one-on-one between members of space crews. Our best hope of survival as a species is to curb our tendency toward conflict and live together peaceably.

Exploration? Oh yes! And I haven’t even mentioned astronomical endeavours like the Hubble and Kepler telescopes that have peered into the farthest depths of the universe and confirmed the existence of planets around other stars.

A Golden Age? Actually, that’s selling it short. This kind of exploration is priceless.