THE BATTLE BETWEEN SPACE FACT AND SPACE FICTION

/

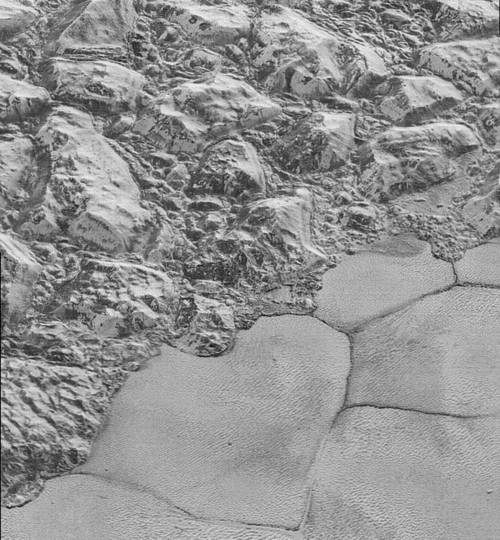

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

We live in an era when a spacecraft can send us pictures of the surface of Pluto that are nearly as good as what we’d see out the window of a jetliner flying over our own planet. Take a look at some of the newest images processed by NASA’s New Horizons team—they’re astonishing. Mountains, gulleys, long running cliffs. As a science fiction writer I could place an astronaut on the dwarf planet, maybe climbing out of his crashed utility ship and hiking toward the nearest outpost, and I could describe real ridges and crevasses he’d have to cross on the Sputnik Planum, foothills and passes between ice mountains that he’d have to traverse. No invention necessary, just a close look at some high resolution photographs. What’s more, I would do that to add authenticity. The downside? No playing fast and loose with Pluto’s geography or geology now that we actually know what it is. If I had written such a story a few years ago I’d be second-guessing myself and wondering if I’d blown it by featuring a feature that’s not really there.

Of course, that’s been the case for stories set on Mars for decades now and the Moon before that. Still, Pluto?

Oh well, at least there are other solar systems to play with, right? Sure, except now with the Kepler Space Telescope and new sensing techniques, scientists have found nearly two thousand planets around other stars (as of this writing the count according to NASA’s Exoplanet Archive is 1,916 confirmed with another nearly 5000 candidates). We know a lot about some of these planets, like roughly how big they are, whether they’re likely gas giants or rocky worlds, how close they are to their sun (giving a good idea of their surface temperature) and sometimes more. I’ve written stories and novel manuscripts that feature an expedition to another star system or even a colony there. Until they’re published I have to keep checking to see that reality hasn’t overtaken fiction—if it suddenly turns out that there are no planets where I’ve placed mine, or even that I’ve put an Earth-type world where there’s actually a Neptune-like planet, some major rewriting would be in order (once they are published I’m stuck eating crow, at least until the next edition!) The writers of the new Star Trek series will have to check the latest stats on each star system before the Enterprise warps in and sends an away team down to the surface of a planet that doesn’t exist, because you’d better believe there are viewers who will check (and probably flame them on social media if they screw up).

As if the situation weren’t tricky enough, the James Webb Space Telescope is scheduled for launch in October 2018 and will not only be able to see small planets that Kepler and the Hubble telescope can’t, it’ll be able to study the atmospheres of planets Kepler can barely detect. That’s power. It will be amazing. It could also be responsible for a sudden rash of science fiction writers with strange patches of missing hair.

You might say, no big deal, we still enjoy stories by Arthur Conan Doyle even though we know there are no hidden plateaus in South America where dinosaurs live. True, but no science fiction writer wants their work to be relegated to that category in their lifetime, believe me.

What’s to be done? I suppose we could set our stories farther and farther away from Earth, decreasing the likelihood that new facts will outdate our old fiction, but to my mind the near impossibility of reaching somewhere like the far side of the galaxy would be a more serious breach of scientific knowledge than the odd invented planet. Perhaps we could create tales of human beings placed a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but then you’re entering the realm of fantasy rather than science fiction (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

Really, though, it’s no different than having to keep up with the amazing progress being made in other branches of science—all we as writers can do is embrace the excitement of new discoveries, be inspired by them, rejoice in our progress as an ever-curious race, and do our level best to get it right. And readers can forgive us our transgressions. We hope.

Here’s to new eras of scientific discovery and great science fiction.