CHRISTMAS IN SPACE

/

The winter solstice is a time of celebration for many faiths and traditions. It has a scientific basis, of course, because humans couldn’t fail to notice that it was the shortest day of the year and the longest night. That in itself isn’t anything to be happy about (especially in the days before reliable fire-making) but at least it was the bottom of the cycle and meant that days would begin to grow longer. In our family we celebrate Christmas, but whatever holiday you celebrate there’s a good chance the focus is on time spent together with family and friends. Christmas can be hard if you’re far from home. Some of us have to travel for business, or stay abroad because of work, or face a military assignment in another country. But picture what it’s like for those who aren’t even on the planet!

Quite a few space missions have been carried out during Christmastime, especially on the International Space Station where astronauts might hang stockings over one of the hatchways arched like a fireplace, eat turkey and cranberry sauce from a plastic pouch or a can, join a Christmas sing-along with Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield and his guitar, and have video chats with their loved ones. Upside-down Christmas trees are a thing aboard the ISS because in zero gravity it keeps them out of the way. Creativity helps if you’re celebrating Christmas in space—the fourth crew of the American Skylab made a Christmas tree out of empty food cans—but a little preparation helps too. The crew of Space Shuttle mission STS-103 in 1999 took Santa hats with them into space, and so have many crews since—not a big deal until you consider that every gram of weight launched into space has a cost in fuel. Obviously someone has decided that fuzzy red hats with pom poms are important to morale.

Physically, astronauts in orbit around the Earth might be only 200 – 400 kilometers from the ground, but their orbits carry them to the far side of the planet and back again. And they must feel far away from their loved ones because of the circumstances. The hazards of re-entry are a barrier that count more than actual distance, and being surrounded by a frozen vacuum while trapped inside a big tin can must seem as isolating as being on a desert island. Live video chats probably help a lot, especially at Christmas. Earlier space crews had to make do with stilted radio conversations, although the time lag from orbit isn’t too bad.

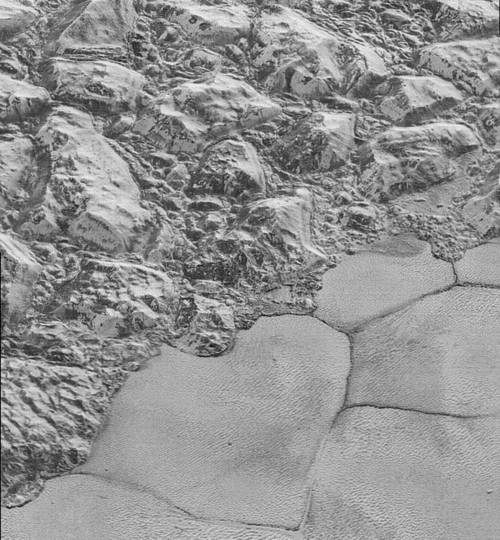

Pity the crew of Apollo 8 who spent Christmas Eve 1968 farther from home than any other humans: 377,000 kilometers away in orbit around the Moon. Talk about isolated. And cramped! Christmas on the far side of the Moon in a floating minivan is not a recipe for a wild party, though definitely historic. They were asked to broadcast a Christmas message back to Earth for the listening public and chose to share a reading from the beginning of the Book of Genesis about the creation of the universe. During that mission they also took the iconic photo of Earthrise over the Moon.

Much as it sounds like a Christmas in space is the last duty any astronaut would want to draw, two things might make it uniquely appropriate. For one, the International Space Station is a terrific example of people from various nations coming together in cooperation and camaraderie, putting aside differences and working toward a brighter future. And secondly, they have the whole universe at their feet, an incomparable view of stars, galaxies, and nebulae, but also the view that moves even the most stoic: seeing our beautiful blue planet with all its inhabitants for the single entity it is. Those two things together are perfect models for the essence of the Christmas season.

Peace on Earth. Good will toward all.

P.S.,

Considering the bizarre realities of Christmas in space, it’s not surprising that Christmas-themed science fiction can be unusual, too, from various quasi-scientific imaginings of Santa’s flight on Christmas Eve (including at the end of time in a story by Greg van Eekhout), to trying to make contact with aliens (“All Seated On The Ground” by Connie Willis), to a classic but sad Arthur C. Clarke story called “The Star” about how a priest on a space mission discovers that the supernova that destroyed a thriving alien civilization was the Star of Bethlehem. (That one always disturbed me, which was probably Clarke’s intent.)

Just Google “Christmas Science Fiction” and you’ll find lots of suggestions. Happy Reading!